The process of collecting, digitizing, and upscaling the original production tapes is a saga deserving of its own article, so we hand over to Mat Van Rhoon to tell you about this compelling side quest: ‘Tex Murphy and the Raiders of the Lost Tapes.‘

Part One: The Hunt

For those of you who know me, you may recall I started out as a Tex Murphy player and fan before I came on board the official development team. However, shortly after the release of Tesla Effect, I inherited the responsibility (alongside Doug Vandegrift) as the series’ archivist. But let’s go back to the beginning of this story…

During Tesla Effect’s production, fellow artist and good friend Bjørn Ottesen and I would spend our “rendering hours” wandering the halls and the warehouse at Big Finish Games after hours. One night we stumbled upon a couple of unlabeled boxes stuffed in the corner of a loft. We discovered dozens of tapes in various formats (Beta SP and SVHS). They were the Tex Murphy production tapes! Putting on our fedoras and testing our detective skills, we made a game of tracking down and cataloging as many tapes as we could find. However, we could only recover 50% of the tapes (observing the labels to determine how many missing tapes remained). Failing to find any additional tapes, we spent our next few weeks performing a quick interim digitization of the tapes we found using the equipment we had available to us at the office, even though we only had around 50% of all tapes. We then re-boxed what we had and stored them away for safe-keeping.

Fast-forward a couple of years, and I decided to reopen the case. After all, if Tex Murphy doesn’t accept failure, why should we? So I decided to have another crack at recovering the remaining tapes. Over two months, I investigated every square inch of the studios and the warehouse, with a fine-tooth-comb, three times over. I found more tapes in the closets, under the stairs, in crates, in cupboards, under desks, and even some in the ceiling. There were even tapes in some of our other warehouses off-site! The next time somebody says “this game is unrealistic, nobody would scatter these objects so haphazardly resulting in such a massive pixel hunt,” I will have words for them. I even found an entire box with a complete collection of Panasonic MII tapes labelled “Pandora B Camera.” Eventually, I managed to recover every single tape from all the games, except TWO from The Pandora Directive.

I would spend another month combing through every location 2 more times looking for these two missing tapes, but after three months in total, I still came up empty-handed. So finally, out of desperation, I walked up to Doug Vandegrift’s office and began interrogating him, Murphy Style.

“When was the last time you saw the tapes?”

“Do you know of any other locations the tapes might be?”

“What can you tell me about Item #186?”

After thoroughly grilling Rook for about 20 minutes, I took a deep breath. I then exhaled and glanced at his workstation.

“Doug?” I asked. “What are you using to prop up your monitor there?”

“Oh? Just some old tape boxes,” he responded.

I took a step closer. “Doug, you wouldn’t mind turning those around so I can see the labels on them, would you?”

Doug reached for his monitor, placed it down onto the desk’s surface, and then rotated the tape boxes. Have you ever felt both eutrophic elation and blind rage at the same time? I hadn’t… until that moment. They were the two missing Pandora tapes! The mix of emotions manifested itself as a slight grimace accented by the occasional eyelid twitch. I took the tapes and left without saying a word.

I now had all the Tex Murphy tapes; no soldier was left behind that day.

Part Two: The Digitization

Collecting the tapes was only the first step in a long process. Anybody who knows the fragility of tape media understands that deterioration is a genuine threat. Thank god for Utah’s warmth and dryness! Most (if not all) the tapes, although haphazardly stored, were in excellent condition. Nevertheless, I decided to enlist the services of a professional to digitize the nearly 160 tapes.

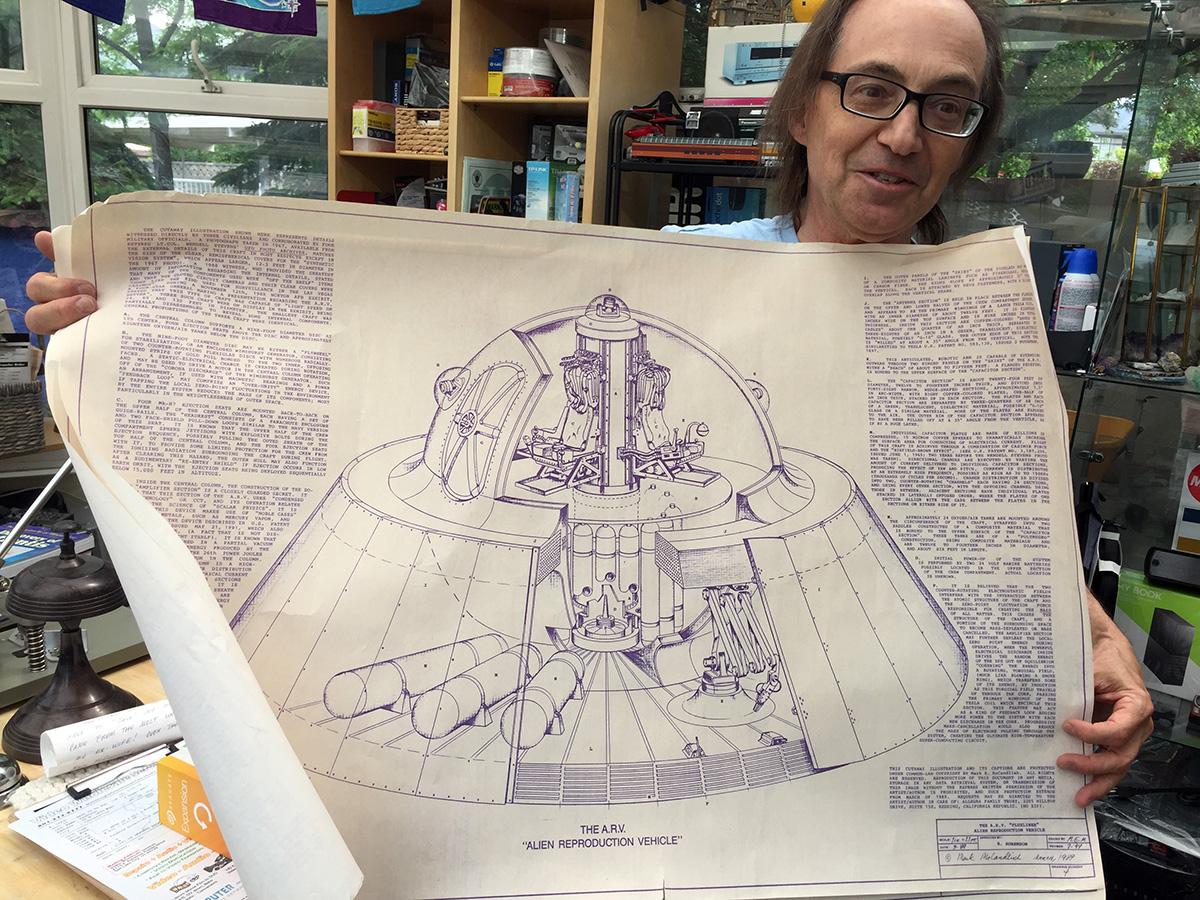

Video Wholesale Services, located in Salt Lake City, would be the team for the job. Their impressive collection of legacy tape-decks and equipment was certainly welcome. It took Mark, our video guru, and his team a handful of weeks to complete the task, and most of it was relatively hassle-free. Did I also mention that Mark is also a real-life Archie Ellis who is actively invested in ufology and was fascinated with the Pandora Directive story?

Overall, the tape digitization process was going smoothly. But we’ve all played a Tex Murphy game before, haven’t we? So we know better than to assume anything would be this easy?

While most of the tapes transferred fine (the Beta SP and SVHS especially), the Panasonic MII tapes didn’t fare so well. Panasonic MII was a metal tape format designed to compete with Beta SP, and was comparable in every regard (you can read more about the format here). The format was used for The Pandora Directive’s “B-camera,” a smaller, more action-oriented camera that made up almost 50% of all the game’s full-motion video content (and most of the closeups), including some of the most important sequences from the game. It was an obscure format. So much so that Video Wholesale Services didn’t have an MII tape deck in their collection. Thankfully, as part of my archival hunt, I was able to recover the original MII deck used on the production of The Pandora Directive (the AU-W35H model). I hauled it over to Video Wholesale Services and we put in our first tape. Unfortunately, the prognosis wasn’t good…

Every tape had this issue. From this output, we surmised two possible outcomes:

- The tape deck was in desperate need of service.

- The tapes had deteriorated.

Refusing to accept the latter prospect (which would mean no chance of recovery), Mark from Video Wholesale Services called a close industry friend who had another, more superior, and well-serviced MII deck (the AU-66H). The next day, it arrived. But there was a catch…

MII tapes came in two formats: large and compact. The Pandora Directive footage was shot on the compact tapes. Most decks were capable of playing both formats (like the deck I had). However, this new unit had been modified to accept the large format tapes only. This is because the tape-loader motor in these decks was notorious for wearing out, and replacement parts were so scarce that fitting a large format mechanism was a more viable option.

So, what did we do with a whole bunch of tapes that weren’t going to fit inside our new tape deck? We made them fit, of course! The larger of the two MII formats use a shell very similar to the standard VHS tape. So, we cracked open one of the MII tapes, transferred, and re-spooled it into a VHS cassette shell as a test. It was tape surgery at its finest…

We then inserted our re-spooled tapes into the new MII unit, but the problem was still there! It must be the tapes! I guess we’re plum out of luck, right?

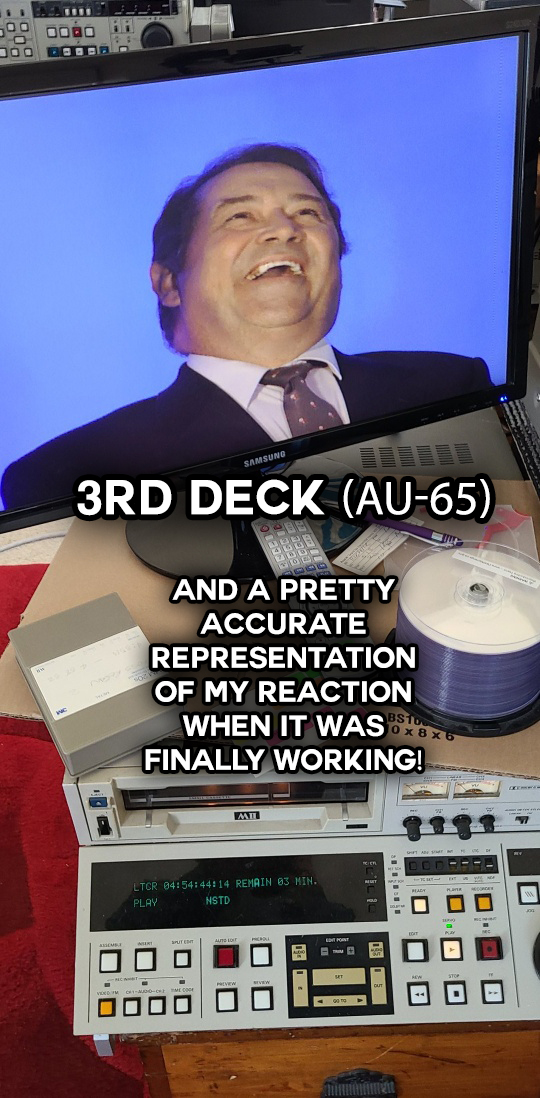

Still not accepting defeat, Mark decided to make a few calls to more industry friends. A few days later, a third MII deck arrived at Video Wholesale Services. This one had come all the way from Rockefeller Plaza in New York City and was originally part of the old NBC Studios (the AU-65 model).

This unit had also been modified to only accept large format tapes, so we put our modified tape inside the third deck, crossed our fingers, and stared at the screen. To our pleasure, the artifacts and glitches were gone! What a relief!

What was the issue?

Inside most tape decks of this kind is a control board that manages “Time Base Correction” (or TBC). This feature is responsible for “reducing or eliminating errors caused by mechanical instability present in analog recordings on mechanical media.” Unfortunately, this board can deteriorate in many decks, resulting in glitching and horizontal shifting shown in the GIF above. Both my original MII deck and 2nd deck had a deteriorated TBC board. The TBC board in the third deck, however, was fine. Overall, it was a much better maintained and serviced unit (having been in a professional television studio for many years).

So, what was the next step? Transfer ALL of the 30 MII tapes into VHS shells and digitize those suckers! After the MII tapes were digitized, we had the complete set of ALL tapes on file. What an adventure!

Part Three: PI meets AI

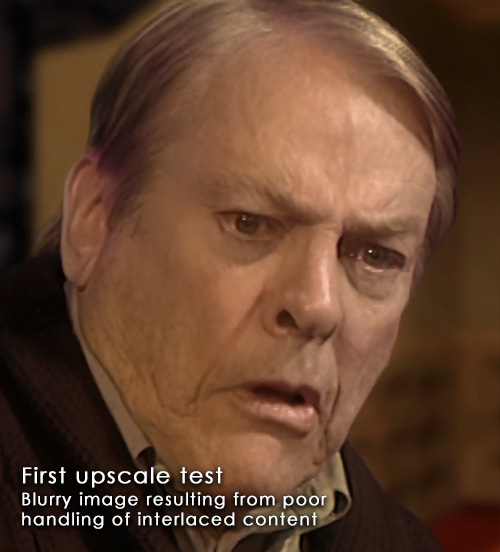

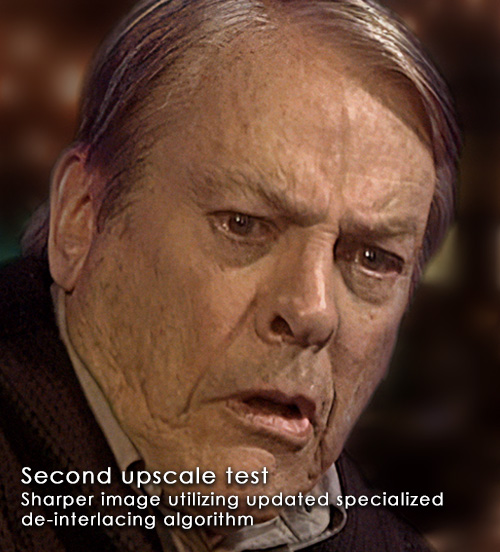

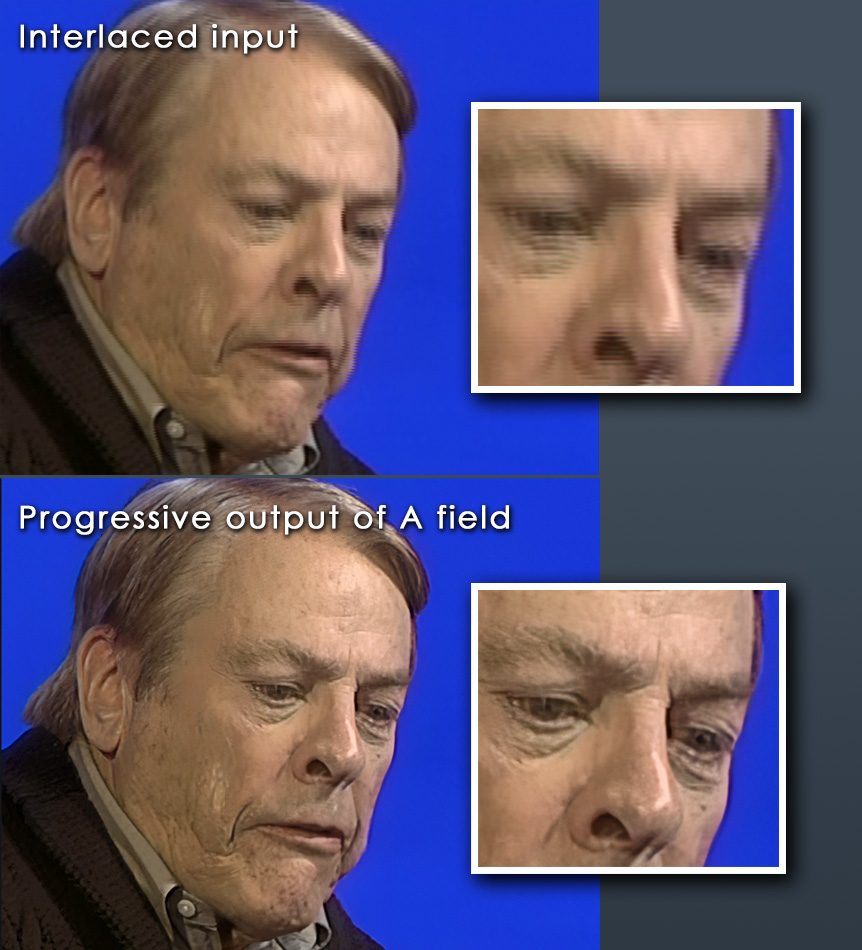

Five years ago, AI and Machine Learning video upscaling was still experimental and often yielded mixed results. Thankfully over the past couple of years, the technology has improved significantly. Still, our source material was going to be a challenge. All of the tapes were recorded in 486i (720 x 486, 30 fps, interlaced at 60Hz). Unfortunately, many AI algorithms don’t like interlaced sources, and early tests with the technology showed promising but still lackluster results. Even when deinterlacing the source content first, it was unsatisfactory.

Realizing that the algorithms still had some teething issues to overcome before they were ready, we put the upscaling process on the back burner for a few months, focusing our attention on other tasks. Then we were alerted to a newly-released algorithm designed explicitly for interlaced source content and immediately jumped back into testing. The results using the new algorithm were night and day…

Note: The backgrounds composited in each of these tests were temporary test backgrounds.

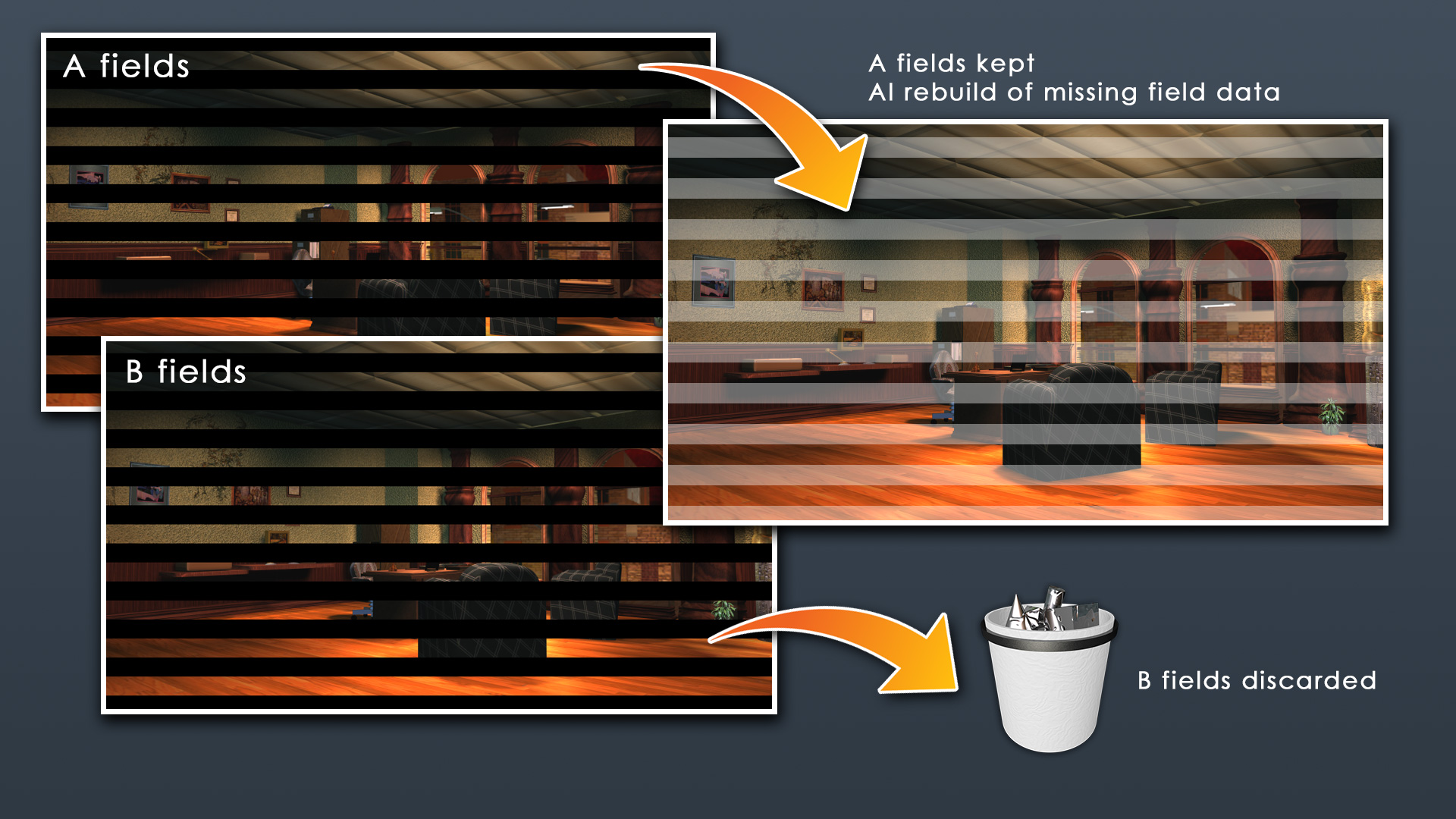

Now we’re in business! After performing a handful of tweaks to the algorithm, we were much happier with the result. However, I noticed something interesting about how the AI system was deinterlacing the footage. Most of the time, deinterlacing is performed by combining what are called “fields.” For every 1 frame of video, there are two interlaced fields. One field occupying all the odd lines of an image, and the other occupying the even lines (also known as “upper” and “lower” fields). These fields are played back at 60Hz to give the illusion of smooth motion while saving on bandwidth (a result of the older technology at the time). But you are only getting 30 full image frames in reality. These two fields are typically combined to produce one single progressive image for deinterlacing, and the images are played back at 30 Hz (or 30fps).

The machine-learning algorithm was performing deinterlacing quite differently. Instead of combining fields, it took a single field and used machine learning to fill in the “blanks” between the interlaced lines on one field, then discarding the other field entirely. The result was an extremely crisp 30 fps output.

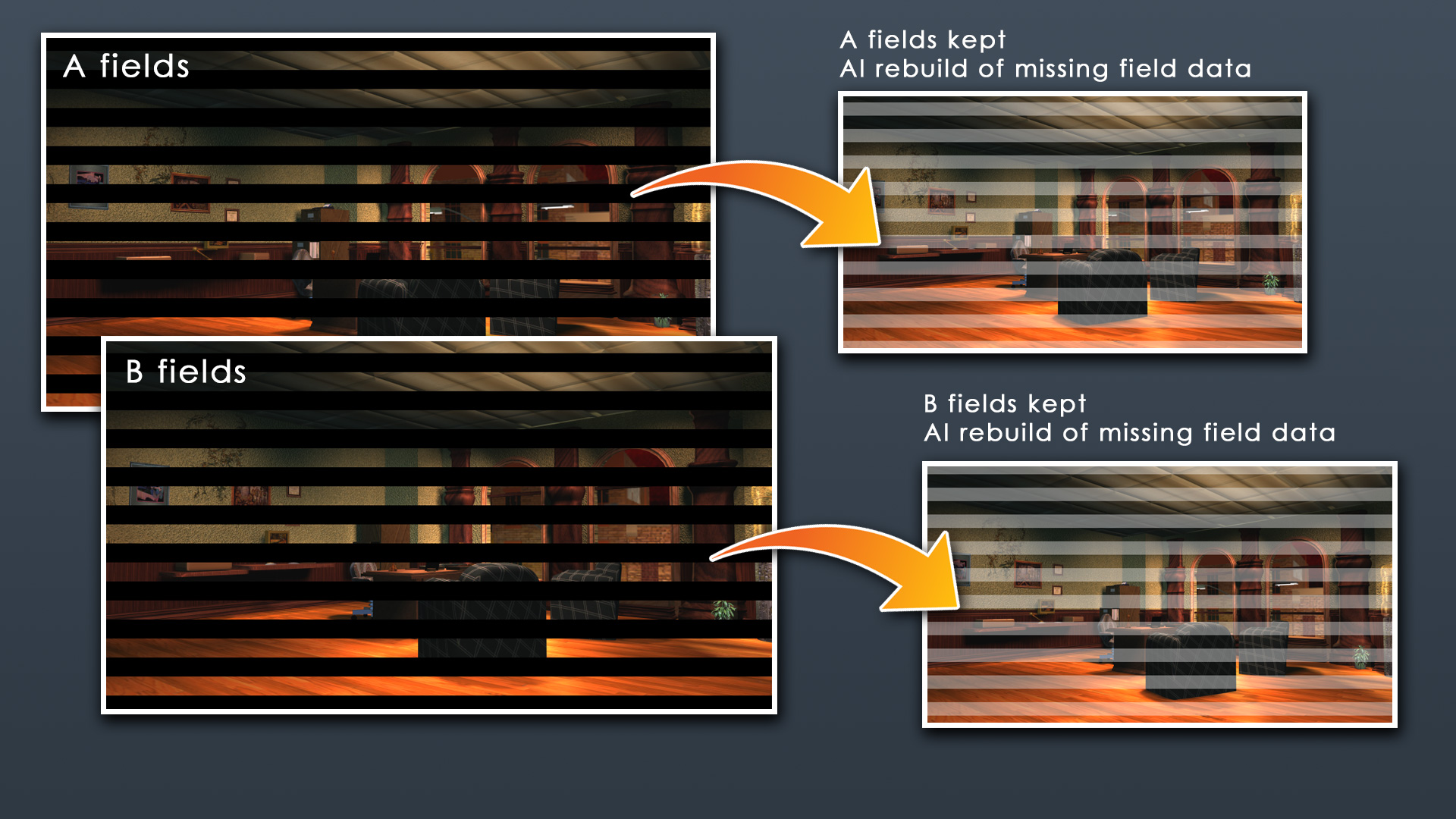

“But hang on a second,” I thought. “Why are we discarding a whole field when we could use the B fields as well?” So I tweaked the algorithm not to discard the B field and perform the same image processing and rebuild those fields as well. The result: A 60 fps progressive sequence fully reconstructed from a 30fps interlaced source!

A few more tweaks here and there and a week’s worth of trial and error, and we managed to successfully produce up to 4K UHD resolution videos in 60fps (progressive) from a standard-definition interlaced source!

Part Four: The Pandora Device

Performing all the Machine Learning and AI upscaling comes at a cost. It requires enormous processing horsepower to pull it off, so we built a machine specifically for this task…

With 20-cores, 128 GB RAM, 20 Terabytes of storage, and the latest Nvidia RTX graphics processing unit, we can perform 4K UHD upscaling of content at around 3-4 frames per second. This results in each tape taking between 7-8 hours to upscale. With over 80 tapes dedicated to The Pandora directive alone, this means the machine will be image-processing non-stop for almost two months! Why did I start this in the summer!? This machine is affectionately referred to as ‘The Pandora Device.’

A fun bit of trivia: A similar workflow took place with Under a Killing Moon back in the day for ingesting and digitizing FMV content. It was performed on a 486 machine which featured an expanded 128 MB of RAM (massive at the time). The RAM upgrade alone cost over $10,000 ($18,700 today when adjusted for inflation). The machine ran so hot that Access Software wizard Dave Brown removed the side panel and directed a desk fan onto the components with an air funnel fashioned out of cardboard. High tech stuff.

Part Five: What comes next?

The machine learning and AI rendering are currently three weeks into their two-month-long haul. In the meantime, I have already begun the reconstruction of all the pre-rendered cinematic 3D environments featured in the game. There are many locations to build, and so far, it has been one hell of a ride faithfully re-creating them while maintaining the soul of the original content.

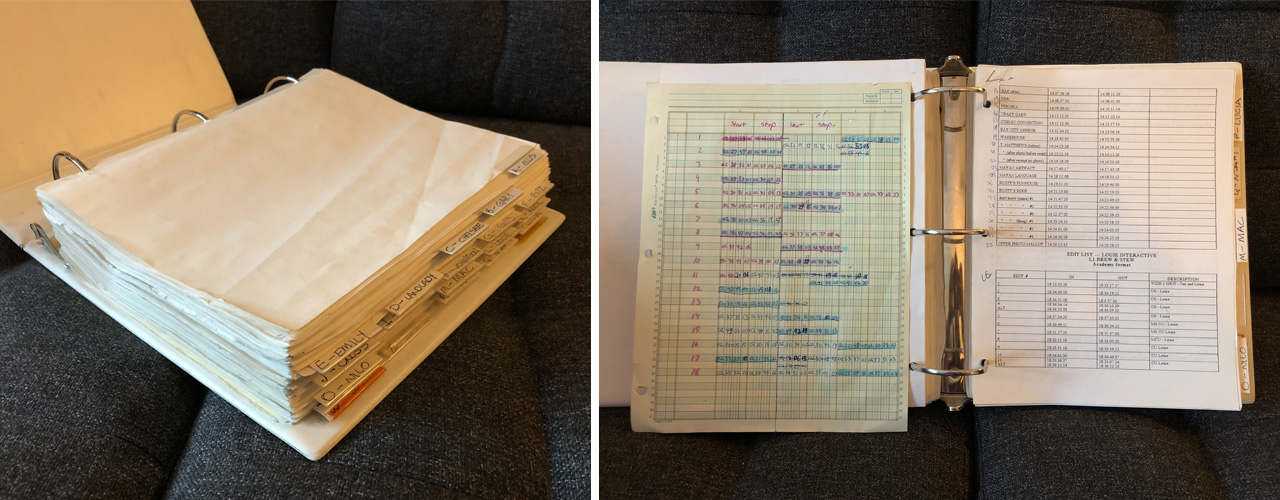

In addition to re-creating the pre-rendered 3D environments, we will need to take the time to painstakingly log all of the upscaled videos and cross-reference them with the game’s final edits to ensure the editing process is both smooth and faithful to the original. As part of the archival hunt I managed to recover the original tape logs and paper edits for the game. Yes, you read that correctly: paper edits. Shortly after directing the shoot, Adrian returned to LA while the tapes and edit suite remained in Salt Lake City. Because non-linear editing workstations were not common in the early 90s (and certainly not readily available on consumer desktops), the folks at Access Software would send tapes and dailies over to Adrian. He would then perform a “paper-edit” of each scene. This involved painstakingly jotting down the timecodes of “in” and “out” points on a shot-by-shot basis. He would then send those notes to the folks in SLC to perform the edits on the workstation. While this process was time-consuming, it certainly was the best fit for the remote nature of the collaboration. Thankfully, things have changed since then!

We can use this phone-book-sized catalog of shots and timecodes to help identify and track down key sequences for the new FMV edits.

But what becomes of the tapes?

We understand the tapes are a source of unspeakable power and have to be researched. And we assure you they will be. We have top men working on them.

Who, you ask?

Top. Men.